Centenary of the Representation of the People Act 1918

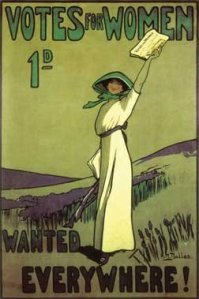

6th February 2018 marks 100 years since the Representation of the People Act, when all women over the age of 30 who met certain property restrictions were granted the vote for the first time. The Act also gave the right to vote to all men over the age of 21. It’s often forgotten that before 1918, around 40% of men in Britain were also denied a vote because of property restrictions. This includes all those hundreds and thousands of men who were called up and died for their country in the horrors of war.

The vote was finally extended to all women over 21 in 1928.

To mark the suffrage centenary, I’m researching a book about the lives of women in Halifax, a former mill town in West Yorkshire. A series of books about women in towns and cities across the country will be published by Pen and Sword at the end of the year.

Looking into the archives to piece together the lives of these Yorkshire women has been fascinating and an eye-opener in so many ways. Below is an article I wrote recently about my research, which was published by a local feminist group in their magazine.

“A Toast to the Ladies”

Celebrating 100 Years of Voting Rights for Women

by Helena Fairfax

I’m not a historian. I write fiction. That is, I write romance – a genre in which women take centre stage. In the 21st century romance novel, the heroine’s independence is taken for granted. She has her own money, she has her own interests and friends, and she’s not looking for a man to look after her or to make her life complete. In fact, in very many romance novels the heroine is the one who “rescues” or transforms the man. My reading and writing habits are so much focused on the world of romance, I simply take for granted that women should be firmly at the centre of their own stories.

Writing a history of the lives of women in Halifax would be a step outside my normal writing sphere, but I accepted it as a challenge. In my naivety, I looked forward to discovering much from the wealth of information I’d no doubt find in the archives.

And this is some of what I discovered: in 1837, a board of 31 men oversaw the operation of Halifax’s workhouses; Edward Akroyd, the millionaire textile manufacturer, was the founder of the first Working Men’s College outside London; Halifax Town Hall was designed by Charles Barry, who designed the Houses of Parliament; John Mackintosh opened his sweet shop in 1890, “and the idea for Mackintosh’s Toffee… came soon after”; the People’s Park was donated by wealthy industrialist Sir Francis Crossley, to “be within the walk of every working man in Halifax; that he shall go to take his stroll there after he has done his hard day’s toil.”

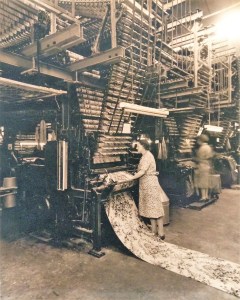

And so it went on. As I leafed through the history books, I began to wonder whether Halifax was entirely populated by men in the nineteenth century. Where on earth had fifty percent of the population disappeared to? While the men were strolling through the park at the end of their working day, what were the women doing? I pictured them at home, still hard at work after their own “hard day’s toil” in the factory, scrubbing floors and mending clothes and feeding the children. I felt them as a completely silent presence in the archives, unrecorded, their mouths bound.

I found a report in a newspaper which I read several times over. On Monday January 14th 1839, a dinner was held at the Odd Fellows’ Hall in Bradford in honour of Mr Peter Bussey, a Chartist and agitator for “universal suffrage”. In those days only the wealthy could vote (and only wealthy men, at that). The Chartists were fighting for the vote to be extended to all men, regardless of income. It was a noble cause, but the terminology still jars, almost two hundred years later. “Universal suffrage”? How could it be “universal” if it didn’t include women?

The Northern Star reports that the evening began with a toast to “The People. The only source of legitimate power”. This is the part I read several times, in order to make sure I fully understood. It’s a worthy toast, but since the dinner ended with a toast to “The Ladies”, I could only draw the conclusion that the “Ladies” were evidently not considered of the “People”. The “People” meant therefore “men only”, and men were therefore “the only source of legitimate power”. The only source? Really? Take a look around the room, gentlemen. In the final irony, the “Ladies” were not even given the opportunity to answer their own toast, which was responded to “in an enthusiastic speech by Mr G.J. Harney of London, who was applauded most warmly”.

The Northern Star reports that the evening began with a toast to “The People. The only source of legitimate power”. This is the part I read several times, in order to make sure I fully understood. It’s a worthy toast, but since the dinner ended with a toast to “The Ladies”, I could only draw the conclusion that the “Ladies” were evidently not considered of the “People”. The “People” meant therefore “men only”, and men were therefore “the only source of legitimate power”. The only source? Really? Take a look around the room, gentlemen. In the final irony, the “Ladies” were not even given the opportunity to answer their own toast, which was responded to “in an enthusiastic speech by Mr G.J. Harney of London, who was applauded most warmly”.

Well done, Mr Harney. There isn’t a single mention of a woman in the entire article, and yet they must have been there. Were they just ghostly figures, shimmering in their evening finery, their mouths opening in vain, unable to make themselves heard?

After weeks of this type of research, I began to discover for myself what Virginia Woolf had described so aptly in her essay on Women and Fiction in 1929. The answer to the history of women’s lives “lies locked in old diaries, stuffed away in old drawers, half-obliterated in the memories of the aged. It is to be found in the lives of the obscure…where the figures of generations of women are so dimly, so fitfully perceived. For very little is known about women. The history of England is the history of the male line, not of the female.”

By peering through the cracks of established sources, and by closing the history books and looking instead for “old diaries”, memoirs, and letters, I have gradually been piecing together a picture of the lives of the women of Halifax.

As I mentioned, I’m no historian. A woman was Prime Minister when I came of age to vote. I grew up with a

cavalier acceptance of my rights. Looking through the archives has made me understand just how far women are from genuine equality, and just how easily everything women worked for could be lost. It’s made me think much more deeply about the countries where women’s voices are still not heard today, and to reflect on all those intelligent, hard-working, tough, spirited women who lived before us, who contributed to the greater good of theirs and our society, and about the deep shame of their being invisible and unacknowledged in the history books.

(And by the way, that recipe for Mackintosh’s toffee that “came soon after” John Mackintosh opened his shop, and which led to a multi-million pound global industry, was invented by his wife, Violet Mackintosh.)

*

Struggle and Suffrage: Women’s Lives in Halifax and the Fight for Equality will be published at the end of 2018/early 2019.

*

I still find it hard to believe that my grandmothers were born at a time when they couldn’t vote, and yet their brothers could. It seems totally incomprehensible to us now. 6th February 1918 is a date to remember indeed…

Leave a Reply